My Journey Towards Self-Sufficiency

What self-sufficiency means to me, how I came to care about it, and how I am trying to become more self-sufficient in my own life.

For me self-sufficiency is not being completely disconnected from the rest of the world whilst surviving nonetheless – although I have done that. But rather, it’s finding a balance between taking care of myself, and having a fulfilling life within the ever expanding modern world. I am not a survivalist that refuses to use power tools or electricity. I am a prepper, but in the most practical sense: I believe that I should have a good understanding of how my everyday amenities work, and that I should have a minimum level of control over my food, water, and power sources.

Sustainability was not on my radar when I was 32. I had recently started rock climbing after being largely exiled from my entire sober social scene. A woman I was dating decided that she would blow up my social life after I broke up with her. That’s a story for another article, but in the wreckage of that breakup, another friend from AA took pity on my situation and invited me to go rock climbing at a local gym.

Now, I didn’t even know rock climbing gyms existed back then. I immediately became obsessed, bouldering every day that my fingertips allowed. After a few months of essentially living at the climbing gym, I was introduced to Connor, a guy living in a van. He opened the door to his Sprinter van and an instant wave of clarity came over me: I want to live in a van and travel around the country. I had to convince my new employer allow me to live in a van and work remotely, and then I would have to build a home into said empty van. My new boss was very cool and I eventually succeeded; I put a down payment on my own Mercedes Sprinter van and started building it into my home.

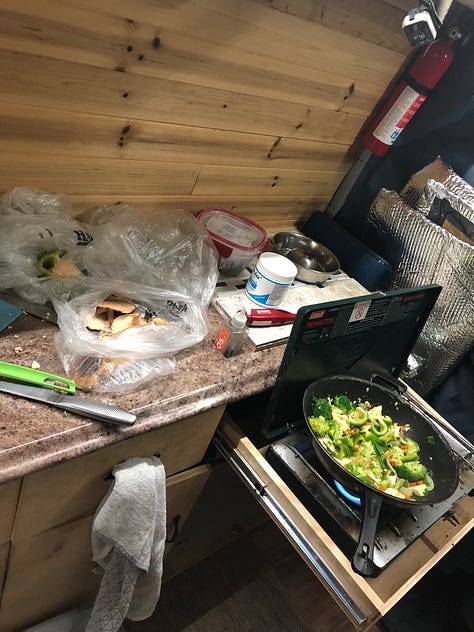

My vanlife adventure brought me away from guaranteed sources for water, electricity, and cooking fuel. No longer could I just rent a home and take those things for granted. That is what ultimately brought me on my current path towards self-sufficiency. Living in the van was easy though: I could go to a supermarket and buy all of those things I just mentioned. It was easy to find the things I needed, but I could also see more intimately how much water, fuel, cooking gas, and food I consumed. No longer were the days of enormous refrigerators or electricity that starts with 120 volts, I became aware of each inch of space in my fridge and every amp hour in my batteries.

I started buying less food and managing my food waste better. The compost went out into nature, along with my grey water and my own human waste. In the beginning I always bought my water from a supermarket, but as I got further out west and befriended numerous hippies, I was shown different ways of doing things. Friends would bring me out into the forest and collect fresh water from natural springs. Eventually, I started looking for mountain springs to collect water on my own. To me, at the time, it just tasted better. I had no way of knowing that drinking spring water would change my entire view of the world.

I was driving a lot. All over the United States. And I was burning a lot of diesel fuel in my van. It didn’t seem right intuitively, to burn all that fuel just to have the adventures I wanted to have. A seed about living on a sailboat had been planted in me during a previous trip – a story for another time – and after breaking my collarbone mountain biking, I found myself laying on a couch, in a house I owned but never intended to live in, wondering what kind of adventure I could line up for after my shoulder healed.

The seed that had been planted inside me unwittingly sprouted. I would learn to sail. I looked on the internet and found a sailing school in Baja California Sur Mexico that had a one-week long sailing course 6 months down the line. I booked a spot, paid a deposit and forgot all about it. I went back to working on my computer and recovering; I had not given it another thought until about a month before the course when the sailing school reached out for the rest of the money. I had recovered from the injury, moved back into my van, and decided in that moment:

Fuck it, here we go.

Life on the sailboat was much different than the van. No longer could I call AAA and get a cheap or free tow to the Mercedes dealership where there was coffee, snacks, WiFi and free rental cars at my disposal (they didn’t even care about giving me a rental car when I had Zoe, my red nose pitbull daughter). On the contrary, when the sailboat broke down in the middle of the ocean and all the currents and wind were pushing me further out to sea, I would need to float and eventually flag down small fishing boats and bribe them to tow me to a sandy shore or the nearest bay where I could drop my anchor safely. From there I would have to leave my boat floating and unattended: insecure to nature and marauders alike. I would make my way to land by paddleboard or inflatable dinghy, sometimes finding myself walking miles just to find the supplies I needed to make repairs and continue the journey.

I bought an old water maker – a reverse osmosis system – from another sailor and we installed it together on my boat. Low pressure pump, high pressure pump, filters, filter housing, distribution manifold and lots of hoses. From then on I was converting seawater into drinking water — at least, when it worked. This was great when I was cruising offshore in crystal clear waters. But when I was moored in a bay with working fishing boats, often the water was filled with motor fluids and fish guts, and not what I wanted running through my filters. Sometimes I would walk with 2 empty five gallon jugs of water in hopes that I could exchange them for 2 full ones at some tiny storefront in the middle of nowhere. Jugs that I would walk back to the beach, one on each shoulder, and transport them to my boat by paddleboard or dinghy. Other times, I would have to have water delivered directly to the boat using giant bins of water and a small pump hooked up to a gasoline generator.

Eventually I realized that sailboats are NOT more sustainable than a van. In fact, they pollute a lot unless you have perfect wind and currents, as you’re in constant need to run your motor; which requires many fluids and always leaks at least a little. Depending on what country you’re sailing in, your human waste can be dispersed directly into any waters, making crowded bays metaphorical toilet tanks, with “floaters” slowly drifting away from the sides of every boat first thing in the morning. I felt fine pooping when it was just me out in the wilderness, but when I entered a more population dense areas, waste management quickly became a glaring concern.

Living off-grid for many years has taught me a lot about finding fresh or clean water sources, solar and battery systems, gas and diesel motors and generators, food sourcing and production, waste management, plumbing and pumps, heating and refrigeration, and basic construction and maintenance of various types of homes whether mobile on wheels, floating in the middle of the ocean, or a 30 minute hike up the side of a volcano.

I have endless ideas and projects in the works. Building a farm and home have taught me many things about becoming self-sufficient. I can see a future where I grow and raise all my own food, and my friends and I help each other build the structures we need on our properties. I can see a future where I don’t need to invest my money but I can invest my time and my energy into the lives of those around me: investing in people instead of things.

For my whole life I have been writing software for my income. And I still will if this writing endeavor never becomes profitable – all of my projects will be finished; it’s just a matter of time. But part of my efforts here are to crowdsource enough money through subscriptions and donations to move my projects forward with more momentum. Evolving the farm and house, as well as building a rock climbing gym and acrobatics center near the beach are at the top of the list. Between the farm and the gym, I trust that my life and livelihood will always feel abundant and blessed.

Sustainability touches all of my projects. At my farmhouse I have a composting toilet, and my grey water goes to watering plants. At the rock climbing gym, since I’ll have flushable toilets, showers, and a spa, I will need to design and build a septic system that can easily be maintained in the future. My farm has fresh natural spring water from high up on the volcano, where my gym requires me to dig a well to reach an underground aquifer.

My next post will be a detailed list of my past, current, and future projects; a deeper look into what my life looks like from day to day and year to year. As I share my projects with you, sustainability will be a big theme. Where do the materials come from? What types of things do I need to consider before I start a new project? How do I minimize energy spent to achieve my goal?